“A bit of science distances one from God, but much science nears one to Him…”

Louis Pasteur

Current Disease Ecology Thoughts

In the recently published article from researchers Molentze and Streicker, 2020, the authors provide findings and supportive reasoning regarding their acceptance of the notion that “special” animal reservoirs of zoonotic viruses should not be attributed to a previously perceived, distinct ecological or immunological relationship between animal taxa and viruses. The authors explain their disagreement in the theory that animal groups, such as rats and bats, specifically, have been widely considered by others to exhibit a higher fitness as viral reservoirs for potentially zoonotic diseases as a result of their physiology, evolutionary history, or, again, their ecological tendencies as Han et al., 2016, have formerly outlined. Furthermore, Han et al. primarily focused on the animal reservoirs and their global distribution, even concluding that the most species-rich orders (Rodentia and Chiroptera) probably appear to harbor the highest diversity of zoonoses. Although Molentze and Streicker reported, “Animal orders of established importance as zoonotic reservoirs including bats and rodents were unexceptional, maintaining numbers of zoonoses that closely matched expectations for mammalian groups of their size”. Ouch.

Olival et al., 2017 concentrated on investigated the actual zoonotic pathogens, reflecting in the author’s more specific discussion of host traits that might predict total viral richness within each mammal species. The authors also express the likeness of bats to be uniquely suited as the reservoir for more zoonotic viruses than any other taxa, due to some distinct behavioral and physiological traits they possess.

In response to this data, I personally (in total honesty) am slow to the reception of a paper with such a strong title associated with such a complex subject matter as seen in Molentze and Streicker’s paper, Viral zoonotic risk is homogenous among taxonomic orders of mammalian and avian reservoir hosts. I find the topic, still, vastly understudied to support such an aggressive statement, despite their extensive data analysis/cross examination within numerous viral families in relation to different animal taxa. However, I do view this study as a valuable addition in the ongoing study of zoonotic disease ecology and think the points raised within this paper should certainly be considered in future research directions (as I do believe this must be studied far more extensively to make such a bold statement).

I also look forward to responses and further research related to this study, especially in the public health surveillance aspect, as it appears we might need to consider widening the scope of suspected animals in zoonoses. This also adds insightful information in the important goal of properly refining strategies in order to successfully identify viruses prior to their emergence within the human population.

I still have a few residual doubts regarding the lack of viral richness in certain animal taxa, as evolution remains to be a force to be reckoned with, especially within the persistence and transmission of viral pathogens. Therefore, in my humble opinion, I find it highly unlikely for certain animals groups not to have participated in the evolution of viral zoonoses.

Kind of looks like my little pupper, Winnie

Supplemental Information

Han et al: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4921293/

Olival et al: https://www.nature.com/articles/nature22975

Mollentze and Streicker: https://www.pnas.org/content/early/2020/04/08/1919176117

Superbug

So far, I have largely concentrated on pathogens that no longer seriously affect us in this modern world. But, of course, there is a price we pay for such luxuries. One of which would be the risk of healthcare-associated pathogens and the accompanying antibacterial resistance, as seen in the evolutionary story of Staphylococcus aureus. S. aureus is a ubiquitous, Gram-positive, bacterium that approximately 30% of the human population carry within their noses and can even be a member of our skin’s microflora. This classifies S. aureus as an opportunistic pathogen, as it generally will not cause illness except in certain cases/under certain conditions, especially within those experiencing weakened immune systems or pre-existing conditions, hence the reason the pathogen generally thrives within hospital and healthcare settings, However, widespread community infections are recently emerging, within the US and worldwide, among healthy individuals.

Although S. aureus is naturally susceptible to almost every antibiotic, ongoing antibiotic resistance is a great cause for concern as the organism can readily gain resistance to multiple antibiotics, therefore limiting treatment options. In fact, it was S. aureus’ exceptional susceptibility that eventually led to the discovery of the first antibiotic, Penicillin, as found by Alexander Fleming. In 1928, the scientist continued his experiment in which he was working with staphylococcal colonies within petri dishes. One of the plates was left opened near a window which began to grow mold. Fleming noted areas of bacterial clearing within proximity to the mold colonies. After isolation and identification of the mold, he learned that all Gram-positive bacteria were susceptible to this “mould juice” produced by the mold colonies. He named his finding “Penicillin”, which marks the beginning of “The Antibiotic Era” (despite penicillin application not occurring until 1940 to treat WWII soldiers, as there was little enthusiasm within the scientific community upon his discovery, initially). Although it was hardly the mid-1940s before penicillin resistant cases of S. aureus were noted within healthcare settings, only a few years into the antibiotic’s introduction into the clinical practice. Within 10 years, resistance was viewed as a significant problem communities were facing.

“I did not invent penicillin. Nature did that. I only discovered it by accident.”

After the introduction of the antibiotic, methicillin, around 1960, resistance to this antimicrobial was almost immediately noted in a published article in 1961 describing the drug resistant strain. In response to earlier penicillin resistance, vancomycin was discovered in the 1950s, but was reserved for patients with serious b-lactam allergies due to perceived toxicity of the newer drug at the time.

Today, there are several different levels of antibiotic resistant S. aureus including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA). Although most have heard “MRSA” all S. aureus are capable of producing infection, MRSA is just often better known. This constantly evolving antibiotic resistance is often possible due to horizontal gene transfer from outside. However, chromosomal mutation and antibiotic selection can also serve as a route of resistance acquisition for bacteria.

Penicillin works against microorganisms in disrupting cell wall synthesis during replication whereas methicillin is a partly synthetic derivative of penicillin, in which a structural modification was added to original penicillin. This modification added protection from the recently evolved bacterial strains containing penicillinase/beta-lactamase, making it resistant to the bacteria’s efforts at breaking down the antibiotic’s essential beta-lactam ring, central to this drug’s antimicrobial activity.

Vancomycin is currently considered the last line of defense against S. aureus, which has also led to the emergence of vancomycin-resistant S. aureus. Vancomycin acts against susceptible bacteria in inhibiting the second stage of cell wall synthesis.

Research continues in understanding the forces that direct evolution of drug-resistant organisms, as they may generally begin within the containment of hospitals, but, through detailed modifications, can arise within our communities as virulent pathogens to harm even the healthiest humans. What we can have an effect on now is to eliminate the overuse (and misuse) of antibiotics, as this is obviously a contributing factor to the rapidly evolving antimicrobial-resistant strains of bacteria.

Furthermore, the innovation of new, rapid diagnostic technologies aid in the proper treatment of infections and are, hopefully, making their way to be widely utilized throughout clinics. Alternatives to antibiotics are also gaining attention of researchers in the treatment of bacterial infections. Although this already exists (in its simplest form) in the prevention of infection by proper hygiene practices and cleanliness.

“When I woke up just after dawn on September 28, 1928, I certainly didn’t plan to revolutionize all medicine by discovering the world’s first antibiotic, or bacteria killer. But I suppose that was exactly what I did.”

-Alexander Fleming

In 1936, Fleming accurately predicated our future by telling colleague and friend, Dr. Bill Frankland, “there will be a revolution, but doctors will overuse it, and because bacteria have to survive – they are very very clever – they will become resistant to it”.

Sources

Andrew Henderson, Graeme R Nimmo, Control of healthcare- and community-associated MRSA: recent progress and persisting challenges, British Medical Bulletin, Volume 125, Issue 1, March 2018, Pages 25–41, https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldx046

Chambers, H., DeLeo, F. Waves of resistance: Staphylococcus aureus in the antibiotic era. Nat Rev Microbiol 7, 629–641 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2200

Chatrchai Watanakunakorn, Mode of action and in-vitro activity of vancomycin , Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, Volume 14, Issue suppl_D, 1984, Pages 7–18, https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/14.suppl_D.7

https://www.cdc.gov/hai/organisms/staph.html

https://www.imperial.ac.uk/news/189049/sir-alexander-fleming-knew-1936-bacteria/

Levine, Donald. (2006). Vancomycin: A History. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 42 Suppl 1. S5-12. 10.1086/491709.

Tan, Siang & Tatsumura, Yvonne. (2015). Alexander Fleming (1881-1955): Discoverer of penicillin. Singapore medical journal. 56. 366-7. 10.11622/smedj.2015105.

Pigs, Worms, and Cysts

The highly successful parasitic tapeworm known as Taenia solium has long been evidenced in human history, with ancient Greek and Chinese recordings. The Greeks correctly recognized the association of widely common intestinal tapeworms with the ingestion of cyst-laden pork. They referred to these “hailstones” in meat as cysticerci (which we still refer to them today), meaning “bladder-tails”.

Today, however, the parasite is closely associated with areas of poverty and poor sanitation practices in its only known definitive host, the human. Although the parasite is present worldwide, it is essentially eliminated in modernized civilizations due to advanced infrastructure and sanitary practices/strict food regulations/inspections (i.e. pigs no longer ingesting human feces containing eggs, and subsequently developing cysticerci which could then be ingested by under-cooked-pork-eating humans, thus perpetuating the parasite’s life cycle). However, T. solium infections are increasing in the United States, specifically due to more prevalent migratory practices of people indigenous to other countries where these infestations are prevalent. With this being said, pork should ALWAYS be thoroughly cooked to at least 160° F. I know (from one upsetting personal experience) there are some of you out there who get pleasure out of pinching off a taste of raw ground meat before cooking it and SHAME ON YOU. WHY? I would genuinely like to hear your perspective. Anyways, there’s my selfish PSA for the week.

T. solium is known in humans as the “pork tapeworm”, as the organism, seen above, is transmitted by ingesting tapeworm larval cysts known as cysticerci in the metacestode stage present in under-cooked, infected pork. The tapeworm parasitizes the gut of the human definitive host causing eggs to be shed in the stool which can then infect themselves and others with another, more serious form of the disease in which the human is then also serving as the intermediate host. What a double whammy! Generally, tapeworm infections are mild and can go unnoticed for long periods, but if the eggs of the tapeworm are ingested by humans or pigs (pigs usually serve as the intermediate host), this can cause an infection known as cysticercosis in which the eggs develop into larvae and form cysts within various organs and tissues. When these invasive larvae enter the central nervous system they can cause dangerous neurological symptoms in humans (neurocysticercosis), including epileptic seizures, which can be fatal.

So how does a parasite sustain this level of success over thousands of years? Regarding parasitic tapeworms and most other successful parasites, in general, they are noted to typically never kill their host, as they only take just enough to allow them to thrive, grow, and have their host remain alive while shedding/spreading eggs in their stool (in this case). The complex coevolution of these two distantly related species (tapeworm and human) is astounding in terms of molecular adaptations, as even currently, different genotypes of T. solium differ regarding which part of the world it is from, and can be divided into two distinct genotypes – Asian/African and Latin American. Furthermore, molecular profiling of a worm from a traveling patient can allow for professionals to trace back to what region of the world the infection was initially acquired.

Individual patients can also exhibit different responses to genetically/geographically similar worms. This differing host response might be what is responsible for the variations noted in worms of different regions of the world. This would also explain different host responses to the same infestations.

The cysticercus, seen above, must survive in the muscle for weeks to months, so it is not surprising that the cysts have developed elaborate mechanisms for evading the pig’s host response. By evolving to evade the host’s immune response in various ways that are just recently beginning to be better understood, cysticerci within swine muscle tissue have very little to no surrounding inflammation. Likewise, the worm within the gastrointestinal tract of a human host has also developed elaborate means of evading destruction by the body’s immune system. The parasite’s paramyocin binds to a complement component of the innate immune system, inhibiting activation. The parasite also secretes a serine protease inhibitor to accomplish the same inhibition.

It has been shown that humans exhibit a scarce or even absent immune response to the ingestion of T. solium eggs, and by the time the body has mounted a sufficient immune response, the the parasite has already begun to transform to the more resistant metacestode form (cysts within tissue). The parasite actively prevents this inflammatory response, which prolongs its survival in the host and continues this suppression until the cysts begin to degenerate within the body, which is what causes the severe onset of inflammation and symptoms. However, cysticerci do have the capability of gently stimulating the body’s immune system in order to use cells as a protein source, while forming taeniaestatin, among other molecules, that interfere with the cells of the innate immune system, essentially paralyzing our natural immune response.

Perhaps the most fascinating article associated with this topic comes from Aguilar-Díaz et al. in which the team explores how host-parasite coevolution (as well as gender-associated selection to this infection) has occurred over time. Moreover, their findings provided evidence on the crosstalk between the host and parasite at both molecular and evolutionary levels. Specifically, the host’s progesterone has a direct effect on the growth of T. solium cysticerci, among other parasitic factors, as well as progesterone mediation by a steroid binding parasite protein. The parasite was shown to exhibit a progesterone binding protein, initially acquiring this adaptation by either horizontal gene transfer, evolution by mimicry, or, perhaps, from common ancestral genes. Much remains to be understood about this fascinating host/parasite relationship. Studies such as these are vital in understanding the complex interactions so that we may, ultimately, provide better anti-helminth drugs to avoid these potentially dangerous infections.

Sources and Supplemental Information

Bobes, Raul & Fragoso, Gladis & Fleury, Agnes & García-Varela, Martín & Sciutto, Edda & Larralde, Carlos & Laclette, Juan. (2014). Evolution, molecular epidemiology and perspectives on the research of taeniid parasites with special emphasis on Taenia solium. Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 23

Muthukumar N. Commentary: Neurocysticercosis: Evolution of our understanding. Neurol India 2017;65:885-7

NAKAO, M., OKAMOTO, M., SAKO, Y., YAMASAKI, H., NAKAYA, K., & ITO, A. (2002). A phylogenetic hypothesis for the distribution of two genotypes of the pig tapeworm Taenia solium worldwide. Parasitology, 124(6), 657-662

Pajuelo MJ, Eguiluz M, Roncal E, Quiñones-García S, Clipman SJ, Calcina J, et al. (2017) Genetic variability of Taenia solium cysticerci recovered from experimentally infected pigs and from naturally infected pigs using microsatellite markers. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 11(12): e0006087

White AC Jr, Tato P, Molinari JL. Host-parasite interactions in Taenia solium cysticercosis. Infectious Agents and Disease 1992;1:185-93

White AC Jr, Robinson P, Kuhn R. Taenia solium cysticercosis: hostparasite interactions and the immune response. Chemical Immunology 1996; 7:66.

https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/cysticercosis/epi.html

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/taeniasis-cysticercosis

White AC Jr, Tato P, Molinari JL. Host-parasite interactions in Taenia solium cysticercosis. Infectious Agents and Disease. 1992 Aug;1(4):185-193.

Gutierrez-Loli, Renzo & Orrego, Miguel & Sevillano Quispe, Oscar & Herrera-Arrasco, Luis & Guerra-Giraldez, Cristina. (2017). MicroRNAs in Taenia solium Neurocysticercosis: Insights as Promising Agents in Host-Parasite Interaction and Their Potential as Biomarkers. Frontiers in Microbiology. 8. 1905. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01905.

Aguilar-Díaz H, Nava-Castro KE, Escobedo G, et al. A novel progesterone receptor membrane component (PGRMC) in the human and swine parasite Taenia solium: implications to the host-parasite relationship. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11(1):161. Published 2018 Mar 9. doi:10.1186/s13071-018-2703-1

Hélène Carabin, Linda Cowan,Theodore Nash, A. Lee Willingham. Estimating the Global Burden of Taenia solium Cysticercosis/Taeniosis. WHO/FAO Collaborating Center for Parasitic Zoonoses The Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University Frederiksberg, Denmark

The Kissing Bug

When you hear “Kissing Bug” maybe your mind goes to something delicate and sweet, like gentle kisses from a colorful butterfly in a meadow. Today, however, I’m going to share with you a story that is a little rougher around the edges – a story of triatomine bugs and the protozoan parasite they can carry called Trypanosoma cruzi. Rather than the traditional butterfly kiss of fluttering your eyelashes on someone’s skin (also a little unsettling), the infected triatomine bug prefers to crawl onto your face once you are asleep at night, bite your face, defecate on you, and leave you to smush the infective feces into the bite when you touch your face from the irritation, which is totally rude and uncalled for. Then, adding insult to injury, once you rub your face, pressing the pathogen into the bite or mucous membranes (eye, nose, or mouth), you can become infected with T. cruzi which is now known as Chagas disease.

Chagas disease was named after a Brazilian physician and scientist, Carlos Chagas, who discovered the disease in 1909. The disease exists only in North and South America, with a majority of cases in rural, poverty-stricken areas of Latin America.

So, what is a method of reducing human infection of Chagas disease in predominant areas? Biodiversity has commonly been associated with the reduced risk of vector-borne diseases to humans, although this is not always straightforward. A very recent paper from Zahid et al. examines the possibility of utilizing zooprophylaxis, or the “decoy effect” in which animals that are poor or dead-end hosts to a pathogen are used to deter the vectors from afflicting humans. In this case, chickens were used in proximity to humans, finding that chickens at an intermediate (rather than short or far distances) distance from humans reduced the parasite prevalence in humans but only “under the condition that the vector birth rate from feeding on chickens is sufficiently low.”

Studies have shown that the presence of infected or at-risk animals within or closely around the household pose a greater risk for contracting the disease – Dogs, cats, guinea pigs, rodents, chickens, as well as some armadillos, skunks, foxes, etc. can serve as hosts for the pathogen and are commonly present within these households or nearby. Specifically, dogs and cats have been shown to be extremely infectious hosts of the pathogen as compared to humans, further stressing their role in the life cycle of the parasite. Education efforts remain in effect to utilize insecticides within the home to divert or kill insect vectors as well as rodent control methods and dog density control around homes.

The Dilution Effect Hypothesis states that greater diversity in potential host species (greater biodiversity) leads to a decrease in human transmissions. The following are assumptions associated with the hypothesis and my answers are based on the current literature regarding Chagas Disease:

- Must be variation in host competence for pathogen

Yes – There is documented variation in host competence among animals. Dogs, cats, rodents, and guinea pigs have been noted to be extremely competent, amplifying hosts as compared to other animals and humans.

2. The host species left in low biodiversity communities must be the highly competent species.

Yes – Regarding the highly competent triatomine vectors and the mammalian hosts, low biodiversity within the population does not appear to be a factor in competence as they also seem to be the only vector.

3. Transmission must be primarily or entirely horizontal, host to host, not from parent to offspring.

No/Yes – Chagas disease can also be transmitted to offspring by congenital transmission (from a pregnant woman to her baby by crossing the placental barrier) although cases are primarily horizontal.

4. The focal host species must interact with a range of other species.

Yes – The triatomine bugs take blood meals from a variety of mammalian hosts depending on the location and habitat.

5. Increased host diversity doesn’t also cause an increase in vector density, or if it does, the increase must be outweighed by the decrease in prevalence of infection among host focal species.

Apparently so – Gottdenker et al. find that, interestingly enough, environmental disturbances such as deforestation, actually increased vector infection with T. cruzi, possibly by altering host community structures to favor hosts that are short-lived with high reproductive rates (like rodents). Oda et al. found that host diversity alterations did not correlate with disease risk.

Due to the answers provided for the five assumptions, I would support that the Dilution Effect Hypothesis is a reasonable approach in Chagas disease relief efforts in that all of the outlined qualifications were positive with the slight exception that the disease can be transmitted vertically. However, seeing as though this is not common due to widespread screening programs in endemic areas, I did not stress the importance much in regard to the dilution effect. Also, to support this conclusion, there are peer-reviewed articles previously and currently examining this possibility and the implementation of properly distanced animals (along with other preventative measures) to reduce the occurrence of human Chagas cases.

Chagas disease is generally not prevalent with origin in the U.S., although the vector can survive in the southern U.S. However, in the U.S., at least 300,000 cases of chronic Chagas disease are estimated among people originally from Latin American countries. One of the signs of infection can sometimes be a swollen eye (seen above), with the eye sometimes serving as the site of entry for the infection, after the triatomine bug bit you and pooped on your face while you slept causing you to push their infected feces into your own eye. Tricking you into finish their dirty deed.

Sources

Gottdenker, Nicole & Chaves, Luis & Calzada, Jose & Saldana, Azael & Carroll, Ron. (2012). Host Life History Strategy, Species Diversity, and Habitat Influence Trypanosoma cruzi Vector Infection in Changing Landscapes. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 6. e1884. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001884.

Gürtler RE, Cécere MC, Petersen RM, Rubel DN, Schweigmann NJ (1993) Chagas disease in north-west Argentina: association between Trypanosoma cruzi parasitaemia in dogs and cats and infection rates in domestic Triatoma infestans. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 87:12–15

Gürtler, Ricardo & Cardinal, Marta Victoria. (2015). Reservoir host competence and the role of domestic and commensal hosts in the transmission of Trypanosoma cruzi. Acta tropica. 151. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2015.05.029.

https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/chagas/

Montgomery, S. P., Parise, M. E., Dotson, E. M., & Bialek, S. R. (2016). What Do We Know About Chagas Disease in the United States?. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene, 95(6), 1225–1227. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.16-0213

Oda, E & Solari, Aldo & Botto-Mahan, C. (2014). Effects of mammal host diversity and density on the infection level of Trypanosoma cruzi in sylvatic kissing bugs. Medical and veterinary entomology. 28. 10.1111/mve.12064.

Orozco, M. M., Enriquez, G. F., Alvarado-Otegui, J. A., Cardinal, M. V., Schijman, A. G., Kitron, U., & Gürtler, R. E. (2013). New sylvatic hosts of Trypanosoma cruzi and their reservoir competence in the humid Chaco of Argentina: a longitudinal study. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene, 88(5), 872–882. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.12-0519

Sandra M. De Urioste-Stone, Pamela M. Pennington, Elizabeth Pellecer, Teresa M. Aguilar, Gabriela Samayoa, Hugo D. Perdomo, Hugo Enríquez, José G. Juárez, Development of a community-based intervention for the control of Chagas disease based on peridomestic animal management: an eco-bio-social perspective, Transactions of The Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, Volume 109, Issue 2, February 2015, Pages 159–167, https://doi.org/10.1093/trstmh/tru202 Zahid, M.H., Kribs, C.M. Decoys and Dilution: The Impact of Incompetent Hosts on Prevalence of Chagas Disease. Bull Math Biol 82, 41 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11538-020-00710-5

COVID-19 – all the facts and none of the panic

As someone who grew up near the Gulf Coast and braved hurricanes that we definitely should have evacuated for (hindsight is 20/20…) I have realized that it takes quite a bit for me to panic regarding natural disasters or public health issues. So, when the University told me to work from home until further notice today (I work in a research lab) due to the coronavirus pandemic, I think it might have sunk in that this is a deep concern. Or maybe it sunk in when I casually went to Wal-Mart on my way home to “just pick up a few essentials, probably not necessary but just in case! hehe!” and, within 20 minutes, was hit with a buggy, cursed at, and witnessed the controlled chaos that this store was that I realized this is serious. Not to make light of the situation at all, don’t misunderstand me because I recognize people have passed and that we all feel scared, but I have realized the most precious invention known to humankind has, no doubt, got to be disposable toilet paper. Never in my life have I witnessed such talk about this modern day essential. Luckily, I was talked into buying a gigantic pack on my last visit by the Wal-Mart lady who gave me some insight into their staff meeting and what items were going next, and my goodness was she right. EMPTY shelves today. But anyways, shout-out to the inventor of toilet paper – I think he would secretly be very pleased if he knew his invention was now only on the black market due to mass hoarding as the #1 item that all humans refuse to live without. Anyways, we have to laugh so we don’t cry sometimes, right?

The novel coronavirus, known as COVID-19 (which stands for coronavirus disease 2019), emerged in December 2019 in Wuhan, China and has recently led the World Health Organization to declare this disease a pandemic. While researchers are quickly learning more about this pathogen, much is still unknown. The source of the virus within the earliest known patients has been linked to a large seafood and live animal market in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, which indicates an initial animal-to-human transmission mechanism. However, to date, no subsequent cases have been associated with this mechanism and zoonotic transmission of the virus has not been documented. A single case of a pet dog in Hong Kong weakly testing positive for the virus did occur, with the dog recently testing negative for the virus after quarantine. Experts agree that there is no evidence that pets can become ill from COVID-19 or that they can transmit it to other animals or humans. Later cases in China were observed in patients who had no link to the market, indicating community or person-to-person spread.

Regarding COVID-19’s high infectiousness, this novel virus has the ability to infect nearly all human beings seeing as though our abundant population is entirely susceptible. Densely populated cities and places of work along with crowded modes of domestic and international travel drive the spread of this virus quickly and with ease.

As of today, COVID-19 is widely distributed across the world, as seen in the global map provided by the CDC, due to these human behaviors.

A complete clinical overview of the symptoms and severity are not fully understood as of now, with patients ranging from asymptomatic to extremely severe and even fatal, specifically in elderly patients and immunocompromised patients of all ages. The incubation period is thought to be between 2-14 days with symptoms including a fever, cough, or shortness of breath.

Gervasi et al. defines host competence as “the proficiency with which a host transmits a parasite to another susceptible host or vector”. Understanding heterogeneity in host competence is an important step in improving our epidemiological predictive capabilities of pathogens, specifically, those with one or more hosts. Humans currently appear to be the main host of this specific pathogen, although it is apparent, due to the origin of the disease in humans, that animal reservoirs do exist. I predict that COVID-19’s origin will be traced back to a bat-to-human initial transmission considering bats are well-documented to carry a widely extensive and diverse repertoire of viruses (and coronaviruses, specifically).

This speaks to the cultural aspect making this spillover possible in China. Once this pandemic is contained, markets such as these along with human interactions with animals and wildlife, and the safety of certain exotic cuisines must be explored so that we can all avoid another worldwide catastrophe such as this.

Presently, it is understood that COVID-19 is transmissible from person-to-person through direct personal contact or through respiratory droplets produced during a cough or sneeze which is currently the aim/focus of mitigation practices and guidelines that are currently in place. Seeing as though we have zero herd or individual immunity within the human population whatsoever to this novel strain, infection is possible for all. However, it is interesting that children have been noted to exhibit low infection rates or even appearing asymptomatic. This can cause the concern for children and asymptomatic carriers of the pathogen to become superspreaders of the disease, with cases of asymptomatic transmission already documented. Those groups or individuals that exhibit this extreme competence can allow the disease to persist and flourish within a population due to the individuals activity and interactions with others not being impeded, thus exposing more susceptible groups at a rapid pace.

As far as alternate routes of transmission, the virus has been detected as being shed in infected patients’ stool, although the virus has not been found to be water or food borne. No cases of fecal-oral transmission has been recorded, though research must continue to elucidate the details of how long the virus can persist in various environments.

So, let’s be smart, stay safe, and breathe, y’all.

And don’t steal the toilet paper from work, I know you’ve all at least thought about it.

Sources

https://www.aappublications.org/news/2020/03/12/coronavirus031220

https://www.avma.org/resources-tools/animal-health-and-welfare/covid-19

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html

https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019

Cascella M, Rajnik M, Cuomo A, et al. Features, Evaluation and Treatment Coronavirus (COVID-19) [Updated 2020 Mar 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020

Gervasi, Stephanie & Civitello, David & Kilvitis, Holly & Martin, Lynn. (2015). The context of host competence: A role for plasticity in host-parasite dynamics. Trends in Parasitology. 31. 10.1016/j.pt.2015.05.002.

Martin, Lynn & Addison, Brianne & Bean, Andrew & Buchanan, Katherine & Crino, Ondi & Eastwood, Justin & Flies, Andrew & Hamede, Rodrigo & Hill, Geoffrey & Klaassen, Marcel & Adrian, Rebecca & Martens, Johanne & Napolitano, Constanza & Narayan, Edward & Peacock, Lee & Peel, Alison & Peters, Anne & Raven, Nynke & Risely, Alice & Grogan, Laura. (2019). Extreme Competence: Keystone Hosts of Infections. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 34. 10.1016/j.tree.2018.12.009.

Smallpox

The variola major virus is the causative agent for the deadly disease we know as smallpox. Thanks to successful global vaccination efforts spearheaded by the World Health Organization (WHO) after the last naturally occurring outbreak in the United States in the late 1940s, smallpox has since been eradicated. This eradication marked the first and only successful elimination of a human disease in the world. The last known naturally occurring case of smallpox was in Somalia in 1977. Since then, a confined/limited outbreak was reported in Birmingham, England in 1978 originating from a laboratory accident, killing one person. The disease was declared eradicated in 1979 and remains eliminated today. However, the viable virus remains in two known high security laboratories – the WHO Collaborating Centre on Smallpox and other poxvirus infections at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Georgia, and at the WHO Collaborating Centre for Orthopoxvirus Diagnosis and Repository for Variola Virus Strains and DNA at the Russian State Research Centre of Virology and Biotechnology in Koltsovo, Russia.

In response to the 9/11 attacks in 2001 as well as the Anthrax spore terrorism incidents, there has been an increased concern as viruses have been used as bioterrorism weapons. The smallpox virus is still regarded as a lethal bioterrorism agent; hopefully never to be unleashed considering that most of the population is susceptible to the disease due to the discontinuation of routine smallpox vaccinations over 40 years ago. Moreover, the smallpox virus is highly contagious, with humans serving as the only known host. If infected, the mortality rate is estimated to be about 30%, with up to 80% of survivors disfigured with the characteristic “pockmarks” on the face and body (deep-pitted scars observed during infection) and/or left completely blind.

Although the origin of smallpox is unknown, recent analysis of three separate 3,000 year old mummies of the Pharaoh Ramses V indicated smallpox-like pustules on the head of the mummies. Worldwide documentation of the disease appears to have been noted ever since this period.

Early control methods involved a process known as “variolation” which was a process of “scraping” the contents of a smallpox pustule onto an uninfected individuals arm or even inhaling the contents. Surprisingly, this early inoculation process, although it did cause the development of symptoms, did result in a lower death rate than those who contracted the virus naturally.

Edward Jenner is widely credited with introducing the first vaccine against smallpox after observing that milkmaids who had developed cowpox did not exhibit any symptoms of smallpox after variolation in 1796. After (quite unethically, yet successfully) experimenting with this idea on his gardener’s 9 year old son, the basis for immunizations was born, leading us to eventually use the vaccinia virus to successfully eradicate smallpox throughout the world. Jenner inoculated the young boy with scab contents of an individual with cowpox (causing him to develop this milder disease) in which he later followed by exposing the boy to pustule contents of a smallpox patient. To Jenner’s amusement, the boy did not develop smallpox after successful exposure to the cowpox virus.

Transmission

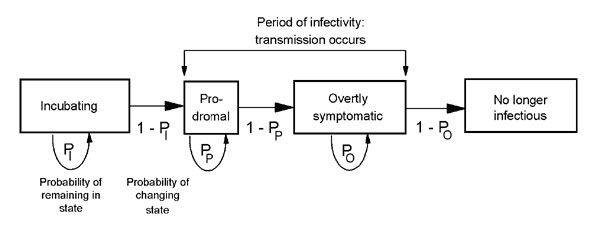

When discussing the transmissibility and epidemiological aspects of smallpox, it is important to understand the various stages and extents of the virus as compiled below by Halloran et al.

The transmission of smallpox can be relatively comparable to that of the more modern-day SARS virus in that they both are spread by close or direct contact with an infected individual or objects. The virus is also capable of being contracted by airborne virus particles. Both of the viruses also have high mortality rates and are known to spread more easily/frequently in hospital and household settings. Transmission modeling of this virus is of particular interest in regards to worst-case scenario preparations (in the event of a smallpox bio-terrorism release). The schematic below from Meltzer et al., produced in 2001, models the person to person transmission of smallpox throughout the stages of the disease.

Various publications have focused on mathematical modelling to predict possible public health measures in the event of a deliberate release of the virus including mass vaccinations, isolation measures, contact tracing with quarantine and vaccination of contacts, as well as ring vaccination around infected individuals. The ring vaccination concept, according to the CDC, “includes isolation of confirmed and suspected smallpox cases with tracing, vaccination, and close surveillance of contacts to these cases as well as vaccination of the household contacts of the contacts”.

Groups have previously utilized the Markov chain model, stochastic simulation of smallpox in a set population focusing on timely mass vaccinations, as well as computer stochastic simulations that stressed the importance of contact tracing and isolation. Others have used a stochastic model predicting that the prior vaccination of healthcare workers might be beneficial.

Castillo-Chavez et al. incorporated the important variable of transient populations on transmission dynamics of smallpox in a more intricate model that I believe should certainly be considered in today’s global culture of highly prevalent travel and migratory tendencies. This group stressed that locally-based control measures would not be sufficient and global policies and approaches to an outbreak would need to occur. Studies focused on strategies to contain local outbreaks after their detection show that timely interventions with vaccination and contact tracing are able to halt transmission. Grais et al. even explored the effectiveness of instituting air travel restrictions as a control measure in the event of a smallpox release.

It was quite interesting to note that most publications I studied for this review were published shortly after the terrorist attack against the U.S. on September 11th, 2001. The years following this compromise on our nation’s safety obviously had (and continues to have) a drastic effect on our understanding and risk perception of potential threats to our public health.

While all this literature is an imperative piece to the puzzle in understanding our ability to predict the outcomes of a smallpox bio-terrorism incident, the aspect of human behavior and our individual propensity to change behavior rapidly must certainly be contributed to this research as examined in the paper by Del Valle et al. Below, this group’s extensive compartmental model taking into account people’s normal contact-activity levels, assuming that their levels are normal before an outbreak and remaining normal until notified that smallpox has arrived in their own community.

The compartmental model visualized in Fig. 7 of smallpox designed by Gonçalves et al. in 2013 incorporates the imperative factor of human mobility patterns.

The figures above provide insight into how much effort has been put forth regarding transmission modelling of the smallpox virus in the case of its use as a bio-terrorism agent; this topic has been, within the past two decades and continues to be, well researched in light of the terroristic threats our country has received. The study of the chain of pathogen transmission from person to person, behavioral and social aspects, as well as the pandemic risk in relation to human mobility/travel patterns have been explored. It should also be noted that almost all of the control methods discussed require a certain medical and public health infrastructure/presence that is not available in all countries. While wealthier and more advanced nations may have the means to control the spread of the disease within their own borders, this is rarely the case in regards to pandemic outbreaks as researchers stress the mobility habits of human beings. Furthermore, due to the prodromal period of the disease, infection would surely spread internationally before officials and healthcare workers are alerted to enforce containment strategies. One particularly concerning factor is the eventual total lack of herd immunity, as previous generations that received the, now, discontinued vaccine are continuing to age.

A key factor essential to the assessment of this risk is Ro, (the basic reproduction number) or the average number of secondary cases infected by each primary case.

R0 has been used to evaluate the severity of an outbreak and the strength of the interventions necessary for control. It is generally accepted that if R0>1, the outbreak generates an epidemic, and if R0<1 the outbreak becomes extinct. The Ro value has been shown to widely vary from historical outbreak accounts, being between 3.5 and 6 before a Nigerian outbreak in 1967 documented to have an Ro value between 4 and 10. This, along with other peer-reviewed literature, poses the concern that Ro may fail at accurately representing a reliable epidemic threshold. Ro should be carefully calculated utilizing many different data (perhaps contact tracing along with previous population level epidemic data and ordinary differential equations) to predict possible transmission mechanisms of a possible future epidemic at the individual level. With this information, I do follow the belief that a smallpox introduction into our population could yield a reasonably rapid epidemic before the intervention of public health implementations. This due, in part, to minimal residual herd immunity since the cessation of smallpox vaccination, the ability for a patient to be infective up to three days prior to the onset of the rash, along with the ease of transmission of the virus from person to person, especially in modern hospital settings, and the basic challenge of targeted vaccination models.

While this is no joking matter, I’ll have someone else leave us on a good note here, because after all, we should celebrate our world’s victory over this disease!

“I was nauseous and tingly all over. I was either in love or I had smallpox.” -Woody Allen

We know now that Woody was probably in love rather than coming down with smallpox, although this may have been a valid thought coming from a teen-aged Woody for those times. And thank God he wasn’t a victim of this horrid disease – he may then have never written one of my favorite movies 😉

Sources

Breban, Romulus & Vardavas, Raffaele & Blower, Sally. (2007). Theory versus Data: How to Calculate R0?. PloS one. 2. e282. 10.1371/journal.pone.0000282.

Burke, Samuel & Epstein, Joshua & Cummings, Derek & Parker, Jon & Cline, Kenneth & Singa, Ramesh & Chakravarty, Shubha. (2006). Individual-based Computational Modeling of Smallpox Epidemic Control Strategies. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 13. 1142-9. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2006.tb01638.x.

CDC; Journal: Emerging Infectious Diseases Article Type: Research; Volume: 7; Issue: 6; Year: 2001; Article ID: 01-0607 DOI: 10.321/eid0706.0607; TOC Head: Research

Costantino, Valentina & Kunasekaran, Mohana & Chughtai, Abrar & MacIntyre, Chandini. (2018). How Valid Are Assumptions About Re-emerging Smallpox? A Systematic Review of Parameters Used in Smallpox Mathematical Models. Military Medicine. 183. 10.1093/milmed/usx092.

Castillo-Chávez, Carlos & Song, Baojun & Zhang, Juan. (2003). An Epidemic Model with Virtual Mass Transportation: The Case of Smallpox in a Large City. 10.1137/1.9780898717518.ch8.

Del Valle, Sara & Hethcote, Herbert & Hyman, James & Castillo-Chávez, Carlos. (2005). Effects of Behavioral Changes in a Smallpox Attack Model. Math Biosci. 195. 228-251. 10.1016/j.mbs.2005.03.006.

Eichner, Martin & Dietz, Klaus. (2003). Transmission Potential of Smallpox: Estimates Based on Detailed Data from an Outbreak. American journal of epidemiology. 158. 110-7. 10.1093/aje/kwg103.

Gani, Raymond & Leach, Steve. (2002). correction: Transmission potential of smallpox in contemporary populations. Nature. 415. 1056-1056. 10.1038/4151056a.

Gonçalves, Bruno & Balcan, Duygu & Vespignani, Alessandro. (2013). Human mobility and the worldwide impact of intentional localized highly pathogenic virus release. Scientific reports. 3. 810. 10.1038/srep00810.

Grais, Rebecca & Ellis, J & Glass, Gregory. (2003). Forecasting the geographical spread of smallpox cases by air travel. Epidemiology and infection. 131. 849-57. 10.1017/S0950268803008811.

Hall, Ian & Egan, Joseph & Barrass, I & Gani, R & Leach, S. (2007). Comparison of smallpox outbreak control strategies using a spatial metapopulation model. Epidemiology and infection. 135. 1133-44. 10.1017/S0950268806007783.

Halloran, M & Longini, Ira & Nizam, Azhar & Yang, Yang. (2002). Containing Bioterrorist Smallpox. Science (New York, N.Y.). 298. 1428-32. 10.1126/science.1074674.

Herfst, Sander & Bohringer, Michael & Karo, Basel & Lawrence, Philip & Lewis, Nicola & Mina, Michael & Russell, Charles & Steel, John & de Swart, Rik & Menge, Christian. (2017). Drivers of airborne human-to-human pathogen transmission. Current Opinion in Virology. 22. 10.1016/j.coviro.2016.11.006.

https://www.1843magazine.com/features/rewind/the-original-antivaxxers

https://www.amnh.org/explore/science-topics/disease-eradication/countdown-to-zero/smallpox

https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/transmission/index.html

Kaplan, Edward & Craft, David & Wein, Lawrence. (2003). Analyzing bioterror response logistics: The case of smallpox. Mathematical biosciences. 185. 33-72. 10.1016/S0025-5564(03)00090-7.

Meltzer, Martin & Damon, Inger & Le Duc, James & Millar, J.. (2001). Meltzer MI, Damon I, LeDuc JW, Millar JD. Modelling potential responses to smallpox as a bioterrorist weapon. Emerging infectious diseases. 7. 959-69. 10.3201/eid0706.010607.

Milton, Donald. (2012). What Was the Primary Mode of Smallpox Transmission? Implications for Biodefense. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology. 2. 150. 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00150.

Nishiura, Hiroshi & Brockmann, Stefan & Eichner, Martin. (2008). Extracting key information from historical data to quantify the transmission dynamics of smallpox. Theoretical biology & medical modelling. 5. 20. 10.1186/1742-4682-5-20.

Slifka, Mark & Hanifin, Jon. (2004). Smallpox: The Basics. Dermatologic clinics. 22. 263-74, vi. 10.1016/j.det.2004.03.002.

Thèves, Catherine & Crubezy, E. & Biagini, Philippe. (2016). History of Smallpox and Its Spread in Human Populations. 10.1128/9781555819170.ch16.

Ring around the rosy, a pocketful of posies

When most people with an American grade school upbringing hear ‘bubonic plague’ our brains probably picture Gothic artistry of skeletons and death from the middle ages depicting the “Black Death”, as we were taught so adamantly by our teachers and world history textbooks. If questioned, I bet we would all buzz in on Jeopardy to answer that “1/3 of the European population” was killed throughout the course of the pandemic.

Or, perhaps you think of this horrifying getup pictured in Fig.2 which was utilized by bubonic plague physicians treating patients, which consisted of a beak-like bird mask which could hold flowers or sweet/strong smelling substances in order to avoid foul odors associated with the disease progression. The beak was also believed to serve as a type of respirator due to their belief that the disease was airborne.

So why are we not all dying from the plague, still, today? Streptomycin and Gentamycin are antibiotics that have both been found to be effective treatments against the causative agent of the plague, the Gram-negative bacterium Yersinia pestis, with streptomycin as the preferred drug of choice for treatment of the plague. Although treatment options are available in the United States, the plague is still defined as a possible bio-terrorism agent.

Where did it come from?

The organism was discovered by bacteriologist Alexandre Yersin of the Institut Pasteur of France during a plague outbreak in Hong Kong in 1894. Originally spreading from Central Asia to Africa and Europe in the 14th century, the plague has caused three known devastating pandemics throughout human history and has reached all continents of the world within the last 150 years. The plague was introduced in the United States in year 1900 by rat-infested steam ships that sailed mostly from Asia, causing epidemics in affected port cities. The last epidemic in our country was from 1924-1925 in Los Angeles. Since then, urban rats have spread the bacteria to rural rodent species, with the bacteria now naturally occurring in various wildlife species including rock, ground, and fox squirrels, prairie dogs, wood rats, and chipmunks in the western U.S. The infection is maintained in wild animal colonies through transmission between rodents by their flea ectoparasites. Y. pestis is an arthropod-borne pathogen that is understood to have recently (within the past 3,000-6,000 years) evolved from Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, a rather benign, enteric pathogen transmitted via the fecal-oral route and widely available in nature in with many animal and environmental hosts. Although Y. pestis is highly similar on a genomic level to Y. pseudotuberculosis, it has recently been found to have the appearance of markedly different mechanisms of disease, niche preferences, and lifestyle due to a series of evolutionary gene loss and gain events. This process has yielded a starkly varied, life threatening, systemic, and specialized pathogen that depends on the rodent/flea transmission cycle. Furthermore, the bacteria heightens its infectious capabilities by its ability to be transmitted from person-to-person once the infection has reached the pulmonary system.

Xenopsylla cheopis (otherwise known as the Oriental rat flea) is the most widespread commensal rodent (mostly rats) flea and is present worldwide. In the U.S., Y. pestis generally circulates between the X. cheopis flea and prairie dogs. Scientists theorize that the plague circulates within these certain rodent populations and their fleas at low rates without causing excessive die off, an enzootic cycle, with the rodents and fleas serving as long-term reservoirs for the bacteria.

How can it be transmitted today?

Y. pestis has evolved to attain a unique set of virulence factors that easily allow fleas to become infected and carry the pathogen (sometimes up to one year) to mammalian hosts. Fleas can become infected two ways – the flea has the capability of transmitting the pathogen the very next time they feed after taking a blood meal from an infected host. The second mechanism of transmission by fleas depends on the ability of Y. pestis to multiply in the flea digestive tract, forming a biofilm in the proventriculus (the valve that connects the esophagus to the midgut of the flea). About 1-2 weeks after the infectious blood meal, the biofilm can grow to impede or block the inward flow of blood while feeding, therefore resulting in the regurgitation of Y. pestis contaminated blood into the bite wound.

Once infected, the pathogen also carries the ability to subvert the host’s immune system, causing rapid death without intervention. With this being said, it is important to note that the sylvatic rodent reservoirs are generally species that are fairly susceptible to the infection, yet resistant to the disease, allowing them to serve as the perfect, persistent reservoir to extend the disease to more susceptible hosts. However, susceptible rodent hosts that succumb to the disease still encourage transmission of the pathogen in that fleas must then find another mammalian host to feed on. This can lead to an epizootic cycle of Y. pestis in which many rodents are infected and die off, forcing hungry fleas to seek other sources of a blood meal such as cats, thus increasing human transmission potentials. There are also present studies investigating the persistence of Y. pestis in the environment as well as post-mortem persistence, which has yielded cases in the past (handling infected animals flesh/fluids after death).

In addition to the bite of an infected flea, Y. pestis can also be transmitted by contact with contaminated fluid or tissue of a plague-infected animal. An example of this could include a hunter skinning an infected rabbit without proper precautionary methods. Septicemic plague can also culminate from a Y. pestis infection, spreading to other parts of the body, turning skin and tissues black and causing tissue death. This is generally observed as a second sign of infection in a patient without proper intervention as swollen, localized lymph nodes (known as buboes) closest to the flea bite generally serve as the first clinical sign. Furthermore, if the bubonic plague infection persists in a patient without treatment, pneumonic plague may develop from the bacteria spreading to the lungs resulting in respiratory failure and shock. Although pneumonic plague cases have not been documented in the U.S. since 1924, it is the most serious form of the disease and the only form of the plague that can be spread person-to-person by coughing/sneezing and inhaling infectious droplets.

Domesticated cats are highly susceptible to the plague – documented cases of cat-associated human plague have occurred in the Western U.S. since 1977. Dogs are also susceptible to the pathogen, yet canine cases are typically rarer, partially due to cats’ tendency to hunt and/or eat wild squirrels, rodents, and rabbits. Infection can be transmitted to humans from their pet cats directly through the inhalation of respiratory droplets coughed by the infected feline or by contact with the cat’s fluids through a scratch or bite. Additionally, cats and dogs can also bring infected fleas into the home, further introducing the possibility of vector-borne transmission to humans.

Evolutionary aspects regarding current transmission

As mentioned above, the emergence of Y. pestis from Y. pseudotuberculosis fits evolutionary theories emphasizing how the new species rapidly evolved by way of ecological opportunities in adaptive diversification. Transmission by the bite of a flea has vastly increased the pathogen’s virulent capabilities, increased its ecological stability, and is believed to be a key evolutionary tactic in the bacteria’s pathogenesis. As spelled out in current scientific literature, the evolutionary mutation process of Y. pestis as a flea borne pathogen includes only a few fundamental gene alterations – gene gain by lateral transfer and gene loss by a loss-of-function mutation (known as pseudogenization).

Pseudogenes are often considered examples of neutral evolution (the passive loss of functional genes that are no longer needed) and can generally be found in higher quantities in the genomes of recently emerged bacterial pathogens. In a recent study, 337 pseudogenes were identified in the genome of a strain of Y. pestis, many of them being metabolic genes of Y. pseudotuberculosis. The presence of these pseudogenes supports the theory of evolution from Y. pseudotuberculosis in the regard that Y. pestis no longer needs this metabolic versatility considering it relies on alternating between two animal hosts. Likewise, a mutational gene loss can be selected for elimination if a functional gene is somehow detrimental to the microbe’s new environment, providing considerable adaptive potential as observed in the evolution of Y. pestis to a flea-borne mode of transmission. However, in regards to gene loss, current evolutionary theory predicts that these mutative events are generally selectively neutral, rather than adaptive, and present in the population due to genetic drift.

In contrast, Y. pestis is believed to have laterally gained two exogenous plasmids from an unknown source after diverging from Y. pseudotuberculosis, acquiring the ability to produce a transmissible infection in the flea, rather than killing the vector as observed in Y. pseudotuberculosis infection of fleas. The Y. pestis flea-borne transmission mechanism is dependent on/characterized by the biofilm formation on the proventriculus of the flea inducing regurgitation of the infected blood meal into another bite wound. The importance of the process has led investigations into the genetic pathways of this characteristic event. Although Y. pseudotuberculosis does not form a biofilm within the flea, it can do so in other environments and the responsible operon for producing and exporting the polysaccharide matrix that makes up the base of the biofilm is identical in both species, further supporting this evolutionary shift theory.

Essentially, four genetic alterations allowed for the evolutionary shift from Y. pseudotuberculosis to the current Y. pestis genotype in which the microbe was able to move up the digestive tract from the hindgut to the midgut (due to the gain of the ‘ymt’ gene), then successfully colonize and occlude the proventricular valve in the foregut (due to the loss of function mutation in the rcsA gene as well as two PDE genes. It has since been concluded that these four genetic alterations sufficiently led to the existing result of regurgitative transmission of Y. pestis in fleas.

Climate

It is a currently accepted trend that occasional plague outbreaks increase in likelihood after wet winters followed by cool summers in particularly arid climates. It has been shown over decades that it is this synergistic index of both cold temperatures and aridity that is imperative in driving an outbreak of the plague, rather that one of the effects alone. Climate studies focused on historical plague transmission in pre-industrialized Europe suggest that neither of these factors seem to have played a role at that time and place. Climate-shaped plague associations appear to be confined to only certain areas, especially in Madagascar, Central Asia, China, as well as the occasional outbreak in the Western U.S. This, along with the understanding of the pathogen’s transmission cycle through rodents, fleas, and humans suggests the need for an immense, multi-faceted outlook regarding climate variability (as well as spatio-temporal and ecological dynamics) on plague transmission.

https://blogs.loc.gov/folklife/2014/07/ring-around-the-rosie-metafolklore-rhyme-and-reason/

As pictured above, many of us have heard that the popular English nursery rhyme, assumed to be of 17th century origin, is thought to be reminiscent of the Black Plague, with “Ring around the rosy” possibly referring to red discoloration around the mouth which could have been caused by systemic plague cases in which blood can pool into the tissues. “Pocket full of posies” referred to the practice of keeping flowers or herbs with them to avoid the smell of death and decay and to ward off the pathogen in a preventative measure. “Ashes, ashes” is actually traced to have evolved from the original verse which read, “A-tishoo! A-tishoo!” which pertained to the pulmonary symptoms of sneezing. “We all fall down!” serves as the grand finale of the game and implicates the death that eventually grasped so many people. I’m not sure who I got it from, and I don’t know if other people my age did the same when they were children, but I was ALL about ‘playing’ “Ring around the rosy” – I would hold my friends’ hands and chant this as we skipped in a circle as little girls. I thought it was loads of fun, and I’m realizing as I’m writing this that I was probably the only one enjoying it that much. Simpler times. And then, unlike the poor populations who actually suffered from the plague, I made everyone get up and do it all over again.

Sources

Cui Y., Song Y. (2016) Genome and Evolution of Yersinia pestis. In: Yang R., Anisimov A. (eds) Yersinia pestis: Retrospective and Perspective. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, vol 918. Springer, Dordrecht

Demeure, Christian & Dussurget, Olivier & Mas, Guillem & Le Guern, Anne-Sophie & Savin, Cyril & Pizarro-Cerdá, Javier. (2019). Yersinia pestis and plague: an updated view on evolution, virulence determinants, immune subversion, vaccination and diagnostics. Microbes and Infection. 21. 10.1016/j.micinf.2019.06.007.

Drancourt, M. & Raoult, D.. (2016). Molecular history of plague. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 22. 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.08.031.

Easterday, W Ryan & Kausrud, Kyrre & Star, Bastiaan & Heier, Lise & Haley, Bradd & Ageyev, Vladimir & Colwell, Rita & Stenseth, Nils Chr. (2011). An additional step in the transmission of Yersinia pestis?. The ISME journal. 6. 231-6. 10.1038/ismej.2011.105.

Eisen, Rebecca & Dennis, David & Gage, Kenneth. (2015). The Role of Early-Phase Transmission in the Spread of Yersinia pestis. Journal of medical entomology. 52. 10.1093/jme/tjv128.

Hinnebusch, B. (2005). The evolution of flea-borne transmission in Yersinia pestis. Current issues in molecular biology. 7. 197-212.

Hinnebusch, B. & Chouikha, Iman & Sun, Yi-Cheng. (2016). Ecological Opportunity, Evolution, and the Emergence of Flea-Borne Plague. Infection and Immunity. 84. IAI.00188-16. 10.1128/IAI.00188-16.

Hinnebusch, B. & Jarrett, Clayton & Bland, David. (2017). “Fleaing” the Plague: Adaptations of Yersinia pestis to Its Insect Vector That Lead to Transmission*. Annual Review of Microbiology. 71. 215-232. 10.1146/annurev-micro-090816-093521.

http://hosted.lib.uiowa.edu/histmed/plague/

Click to access PlagueEcologyUS.pdf

https://www.cdc.gov/plague/transmission/index.html

Kassem, Ahmed & Tengelsen, Leslie & Atkins, Brandon & Link, Kimberly & Taylor, Mike & Peterson, Erin & Machado, Ashley & Carter, Kris & Hutton, Scott & Turner, Kathryn & Hahn, Christine. (2016). Notes from the Field : Plague in Domestic Cats — Idaho, 2016. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 65. 1378-1379. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6548a5.

Poland D. Jack, Dennis D.T. Treatment of the Plague. WHO/CDS/CSR/EDC/99.2 Plague Manual Epidemiology, Distribution, Surveillance and Control

Rasmussen, Simon & Allentoft, Morten & Nielsen, Kasper & Orlando, Ludovic & Sikora, Martin & Sjögren, Karl-Göran & Pedersen, Anders & Schubert, Mikkel & Van Dam, Alex & Kapel, Christian & Nielsen, Henrik & Brunak, Søren & Avetisyan, Pavel & Epimakhov, A.V. & Khalyapin, Mikhail & Gnuni, Artak & Kriiska, Aivar & Lasak, Irena & Metspalu, Mait & Willerslev, Eske. (2015). Early Divergent Strains of Yersinia pestis in Eurasia 5,000 Years Ago. Cell. 163. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.009.

Stock, Ingo. (2014). Yersinia pestis and plague – An update. Medizinische Monatsschrift für Pharmazeuten. 37. 441-8; quiz 449.

Sun, Yi-Cheng & Jarrett, Clayton & Bosio, Christoher & Hinnebusch, B. (2014). Retracing the Evolutionary Path that Led to Flea-Borne Transmission of Yersinia pestis. Cell host & microbe. 15. 578-86. 10.1016/j.chom.2014.04.003.

Yue, Pak Hong & Lee, Harry. (2018). Pre-industrial plague transmission is mediated by the synergistic effect of temperature and aridity index. BMC infectious diseases. 18. 134. 10.1186/s12879-018-3045-5.

What could you say unites all human beings? Love, death, humanity itself? I am going to go out on a limb and provide another suggestion… There is one encounter that every adult human has probably experienced that has the brute force to link us all together – that, my friends, is the complete and utter misery of contracting a stomach virus. It is a visceral experience that can push even the strongest individuals to their knees telling God that it might be time to take them home.

A couple of weeks ago I gave a brief warning about the possible transmission of salmonella from amphibians and reptiles to humans and this week, I would like to expand on this subject considering salmonella is among the infectious pathogens can cause the aforementioned despair. Enteric illnesses are quite important in terms of public health, being the second largest source of communicable diseases worldwide. Salmonella, although lesser known for this type of transmission, is especially interesting in that in can act as a zoonotic pathogen (pathogens that can be transmitted from vertebrate animals to humans). With this being said, salmonella is currently a possible spillover concern for humans and certainly for other animals. Recent findings of wild birds as a suspected source for human salmonella infections have caused a big stir. Not only has this discovery caused a certain public health scare, but it has also brought up concern for the ecological aspect of the afflicted birds. Prevention efforts to reduce further spillover of the pathogen have included various deterrents and demolition of the birds’ (and countless other animals’) habitats. Due to Salmonella spp. causing significant avian mortality, the downstream effects are coming into concern as well as conservation discussions regarding the infected wildlife species.

In a recent paper published by Smith et al., 33% of North American breeding bird species were tested for Salmonella spp. and found that a prevalence of 6.4% of those birds were positive. However, the study of salmonella spilling over from birds to humans is vast, complex, and data intensive feat that must be researched further to have a more complete viewpoint. Furthermore, transmission might not be that easy seeing as though the bacteria must survive in the feces of the bird long enough for human ingestion.

However, salmonella is well documented to spread among wildlife hosts and can depend on multiple exposure and infection routes, although it is typically spread through the fecal oral route. Cross-species spillover of salmonella has also been documented/confirmed in domesticated cats in Switzerland with a history of presumed consumption of passerine birds. The die off of the passerine birds was documented in 2010, was confirmed to be caused by Salmonella enterica, then causing the spillover to cats due to predation.

Due to the fairly novel study of salmonella spillover and spread from birds, I find that the scientific community much attain a great amount more data to be able to draw any conclusions about the disease ecology associated with wildlife carriers and risks of Salmonella spp. It appears that the cases provided in current literature of salmonella outbreaks in birds and spillover to other animals and/or humans has always resolved on its own without the need for intense intervention. We must now conduct studies looking into the epidemiological factors influencing the pathogen within the avian hosts. Things to consider are migration patterns based on weather, food, and the repercussions of different environments/latitudes on the infection in bird populations, as well the role humans might play to perpetrate the disease, such as providing feeding stations where birds might crowd, enhancing the disease transmission.

I hope this has provided a bit of insight into the salmonella bacterium and how even poor little animals can suffer from it just like us. If nothing else, know that you can possibly transmit it from ingesting bird droppings in addition to the classic warnings of “don’t drink raw eggs” or “cook your chicken thoroughly”! I also will add my personal salmonella warning for a second time to not kiss frogs, please.

Sources

Becker, Daniel & Teitelbaum, Claire & Murray, Maureen & Curry, Shannon & Welch, Catherine & Ellison, Taylor & Adams, Henry & Rozier, R. & Lipp, Erin & Hernandez, Sonia & Altizer, Sonia & Hall, Richard. (2018). Assessing the contributions of intraspecific and environmental sources of infection in urban wildlife: Salmonella enterica and white ibis as a case study. Journal of The Royal Society Interface. 15. 20180654. 10.1098/rsif.2018.0654.

Giovannini, S & Pewsner, Mirjam & Hüssy, D & Hächler, Herbert & Ryser-Degiorgis, Marie-Pierre & Hirschheydt, J & Origgi, Francesco. (2012). Epidemic of Salmonellosis in Passerine Birds in Switzerland With Spillover to Domestic Cats. Veterinary pathology. 50. 10.1177/0300985812465328.

Plowright, Raina & Parrish, Colin & Mccallum, Hamish & Hudson, Peter & Ko, Albert & Graham, Andrea & Lloyd-Smith, James. (2017). Pathways to zoonotic spillover. Nature reviews. Microbiology. 15. 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.45.

Smith, Olivia & Snyder, William & Owen, Jeb. (2020). Are we overestimating risk of enteric pathogen spillover from wild birds to humans?. Biological Reviews. 10.1111/brv.12581.

Best Doggone Dog in the West

If you’re like me and watched Old Yeller on repeat as a child (and as in “repeat” I mean walk to the TV and take the 3 minutes to rewind the VCR tape to re-watch), then you learned two important lessons early in life: (1.) avoid wild hogs at all costs and (2.) rabies can be a real threat that is horrifying on many different levels.

In rural Texas in the 1860s where the movie plot is set, rabies was still a prominent threat in America. In several scenes throughout the movie, we note peoples’ various warnings of the “hydrophobia” epidemic in nearby wildlife and even watched as one of the family’s cows suffered from a rabies infection due to a wildlife encounter. The virus was, indeed, extensive throughout wildlife populations, thereby affecting humans and domesticated animals before prevention campaigns took place in the mid-20th century in America.

Rabies is characterized as an infectious, zoonotic (spread between animals and humans), viral pathogen that targets the central nervous system of the body and, if left untreated, is fatal in almost 100% of cases. Although rabies can infect all mammals, bats, raccoons, skunks, foxes, and even mongooses in Puerto Rico have been found to serve as key reservoirs of rabies variants. In warm-blooded hosts, rabies induces acute progressive encephalitis (without swift medical attention in humans), which is what will ultimately kill the host. The signs and symptoms may not appear for up to weeks or even months, with the incubation period of rabies varying greatly. There has even been one documented/confirmed case of a patient not exhibiting symptoms until 7 years after exposure to the virus!

Fig. 1 – The critters above (foxes, bats, skunks, and raccoons) all serve as primary reservoirs for slightly differentiated variants of the rabies virus. Although cross-species transmission certainly occurs (an example being raccoons rabies variant infecting canines) the variants are primarily transmitted within a single species that is the reservoir of that variant. cdc.gov

Symptoms of infection can be nonspecific in the beginning including lethargy, fever, vomiting, and anorexia in animals. However, within days the neurotropic virus progresses to cerebral dysfunction, cranial nerve dysfunction, ataxia, weakness, paralysis, seizures, difficulty breathing, difficulty swallowing, excessive salivation, abnormal behavior, aggression, and/or self-mutilation. I, personally, am astounded at the pathogenicity of the virus, ultimately compelling its host to spread the disease by modifying its behavior, becoming far more aggressive and fearless.

The virus is transmitted through direct contact from an infected animal. Examples of this direct contact include exposure through a bite or scratch from a rabid animal, or through mucous membranes or open wounds coming into contact with the saliva or nervous system tissue from an infected animal. The virus, however, cannot withstand exposure outside the body and is considered to be noninfectious after drying out or coming into contact with sunlight.

According to the CDC, wild animals account for 91% of reported rabies cases in 2017, with bats as the most frequently reported rabid animal having been reported in all states except Hawaii. Nevertheless, it should be noted that the vast majority of the bat population in America (94%) is uninfected.

Getting back to Old Yeller, the movie realistically depicted how before the mid-20th century rabies was a widespread concern for humans and their domesticated animals. It was common for dogs to transmit the disease from contact with rabid wild animals – that is until the early 1940s, when mass vaccination campaigns were employed in the U.S. and continued through to the 70s along with the implementation of strict leash laws for canine pets. Together, this yielded a significant decrease in dog and human rabies cases. Today, the U.S. is considered canine rabies virus variant free. This elimination is still considered one of the greatest public health achievements in the U.S. of the last century, only having 1-3 human cases of rabies per year as opposed to 30-50 human cases per year as seen in the early 20th century.

Although we have successfully observed a decrease in domestic animal rabies cases, wildlife rabies cases have reportedly increased significantly. However, this could be due to better detection capabilities (improved surveillance and laboratory testing) or perhaps, increased human contact with wild animals. Currently, one of the ongoing hurdles research scientists face concerning the study of rabies is that, despite the availability of numerous animal models, the findings seen in vitro with laboratory strains of the virus do not reflect in vivo findings with wild-type strain. Furthermore, widespread vaccination of some wild animals, such as bats, is currently not feasible. Although, in encouraging news, the CDC has recently developed a new rabies rapid test for animal and human cases, allowing potentially infected patients to forgo the usually necessary 4-week regiment of shots for people or euthanasia/isolation in negative animal cases. The LN34 test produces extremely accurate results that can be easily utilized with already existing testing platforms and even foreign countries without the need for specific training.

In, no doubt, one of the most heartbreaking and dramatic scenes in cinematic history (I will argue this with anyone), Old Yeller is bitten while protecting the family from a rabid wolf and isolated by the family to monitor if rabies symptoms arise. Sadly enough, Old Yeller began to exhibit symptoms of aggression and poor Travis realized he had no choice but to put down his beloved dog. Unfortunately, modern day treatment for pets (rabies post-exposure prophylactic is only for human use and very expensive) is not so different from what Travis was subjected to. Previously vaccinated pets can be re-vaccinated and observed for 45 days. However, animals already showing rabies symptoms must be euthanized immediately, reported, and tissues submitted for testing.

I’d like to end this on a positive note, though…and we have good reason to. Thankfully, due to the elimination efforts of the past century, rabies is already a considerably reduced concern for the wellbeing of ourselves, livestock, pets, and hopefully in the near future for wildlife populations. According to the USDA, “every year, federal, state, and local governments in our country distribute more than 10 million oral rabies vaccine (ORV) baits to reduce wildlife rabies and prevent disease transmission to humans, domestic animals, and pets”. These efforts to one day eliminate wildlife rabies variants is well worth the money being spent, with rabies associated costs totaling hundreds of millions of dollars in things like public health investigations, animal rabies tests, pre- or post-exposure prophylaxis, pet and livestock vaccinations, and public education efforts. Although America’s control of rabies is vastly improved, keep in mind that about 38,000 people still receive prophylactic treatments annually, resulting in over $150 million in health care costs.

So with all this information on rabies, I recommend you first, make sure all your pets are vaccinated, then watch *and sing along to* the best theme song to any movie ever made.

Sources and Supplemental Information

Berger, Franck & Desplanches, Noëlle & Baillargeaux, Sylvie & Joubert, Michel & Miller, Manuelle & Ribadeau Dumas, Florence & Spiegel, André & Bourhy, Hervé. (2013). Rabies Risk: Difficulties Encountered during Management of Grouped Cases of Bat Bites in 2 Isolated Villages in French Guiana. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 7. e2258. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002258.

Dyer, Jessie & Yager, Pamela & Orciari, Lillian & Greenberg, Lauren & Wallace, Ryan & Hanlon, Cathleen & Blanton, Jesse. (2014). Rabies surveillance in the United States during 2013. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 245. 1111-1123. 10.2460/javma.245.10.1111.